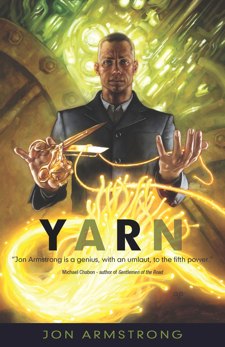

Please enjoy this excerpt from new science fiction “fashionpunk” novel Yarn by Jon Armstrong, out today from Night Shade Books!

Yarn

I woke early, suffocated by a sweaty and prickling sense of apprehension—exactly the feeling of wool against the skin on a warm day. Yet there, in the dark of my bedroom, the sun seemed impossibly far away. What had set this fear in my veins? None of my current design projects were so difficult or important. I was using a new half-micron twill for a suit, but I had tested the fabric extensively and knew its properties. And though the motor-driven ball gown we were creating was complicated, my assistant and I had spent a whole day installing the mechanics and testing it again and again. No, those projects were essentially complete, and I felt good about their look, materials, and function.

It was no use. Neither sleep nor an answer was forthcoming. I rose, wrapped in swirling unease, and prepared for the day. It was still dark as I drove through the obsidian and gold towers of Ros Begas to the studio. And as I walked the two-hundred-meter metal-and-wood meditation-and-exhibition entry hallway that spiraled in from the building entrance to my showroom front door, I went over the fashion consultations I had scheduled for the day, the calls I needed to make to suppliers, the fabric tests I needed to run, and the gathering swarm of details for an upcoming show. In the hallway, I powered-on the fashion exhibits that I had on display: including two fabric bursting automatons and a pilling analysis machine, and stooped to collect a few dust fibers on the dark wood floor.

At the end of the spiral, I paused at a display that held the yarn I had gotten from my father. It rested on black velvet and was lit with a single heterojunction crystal which bathed the thread with a warm, otherworldly glow, recalling the dawn when I’d pulled this strand from my father’s pocket so many years ago. But my memories could not linger because someone or something was lurking beyond the next curve, near the showroom doors.

* * *

Peeking around the last swell of the wall, I saw a figure draped head-to-toe with dark fabric—the weave was a deep dark charcoal green, with the slight sheen like L-flax—a fiber I never used. While it wasn’t completely unusual for someone to come unannounced, the hour and the dress were suspect. Tentatively, I stepped forward, waiting for the visitor to move or speak. At ten feet away, I stopped and as the milliseconds ticked by in silence, began to fear that this was some sort of an attack, that this laundry pile covered an assassin. But even as I catalogued the properties of my jacket, titled Water Hold #11, with both fluid dynamics and charged particle closures, and thought how I might use it to defend myself, my fear seemed misplaced and wrong. I wet my lips. “The showroom is by appointment only.”

The head turned slightly. The voice that emerged was tatty and frail. “I lived a fool’s life and will come to a fool’s end, but I’ve come to ask a favor.”

The skin on my neck and back puckered with goosebumps. “Vada!” The heels of my Celine-Audis clapped percussive notes on the polished wood. “I never thought I’d see you again. Where have you been? What happened? What are you wearing?”

The outline of an arm came away from the torso and touched the door. A moment later after a small, moist click of what I imagined were her gaunt lips, she said, “I’m sorry. I am dying.”

My throat tightened. “No.” As though simple denial changed anything. She didn’t reply. “Where have you been? What happened?”

“I need help.”

“Of course,” I said. “What happened? Are you in pain?” Without thinking, I reached my hand to hers.

She shrank back, shaking her head. “I need your help.”

Anew, I saw the rumpled, rough material that covered her in contrast to the faultless cut, fine texture, and precise stitching of my garments. Shame flooded me. “I never expected to see you again.”

“I had my battles, my deceptions, and my gardens of failure.” She spoke like it was her slogan.

I gazed where I imagined were her eyes. “I tried to find you. I even hired a detective, but he found nothing.” I wished I could see her face. “Three weeks ago, I was in Kong. You’d never believe it, but there’re fifty chrome towers and solar plots there on that old muddy hill. It’s completely different.”

The cloth shook as she nodded. “You look good, Tane. I’m sorry, but I can’t stay. They’re closing in.”

I wondered what she was running from this time. “You must be hungry… allow me to at least feed you.”

Beneath the cloth, she straightened. “I need a Xi coat.”

Xi yarn. Old, immoral, and drug-infused yarn. “That’s not a cure.” I gestured at the materials of the hallway as evidence of my wealth: the rare lumber, the hand-poured high-carbon concrete, and the custom-built fabric test machines. “What do you really need, Vada? Surgery? I can get satellite organs.”

Her head leaned forward. Wrinkles of the fabric covered her face. “They’re just… No. I can’t go on.” Her words were so quiet I barely heard. “It’s time… I just need pure.”

She meant pure Xi, the loving, the universal, the erotic, and the dreaming Xi as opposed to the other kind: dark Xi, skreem Xi, nightmare Xi. It occurred to me that she was wearing the basketweave not so much to hide from the authorities but because she had been disfigured by torture. “Listen,” I said, stooping to meet her hidden eyes, “come in and sit. Whoever is after you… I’m sure we have a few moments.” I reached for where I thought I would find her wrist or forearm, but bumped into what was probably her hip and pulled back.

The pile of basketweave turned as if to leave. “Vada,” I began, “I guess I was looking for you because… I have been thinking about us. The truth is, in some way, there’s been no one else.”

“I hope you weren’t waiting for me!”

“No.” I felt small, though the truth was I had not. “I just mean that…” I stopped and chided myself for trying to explain.

“Tane… I’m sorry. I understand.” Her voice warmed. “I think of you, too. We had an incredible affair.”

She had overstated it. “We had eight months,” I corrected her. “Two hundred and forty outfits and costumes in about as many days.” I tried to keep my tone light, but felt it strain.

“You know who I am.”

I nodded and smiled politely. It was always about who she was.

In the stillness of the hallway, I could hear her swallow. “I’ve heard about you and your work. I’m proud of you. You’ve made wonderful things.” She seemed to laugh for an instant, but then I heard what I thought was a tiny, clenched grunt. She was still for a long moment, and when she finally inhaled a convex of the fabric formed over her mouth.

I stepped toward her, fearful she might collapse, but she backed away.

“Can you please make me a Xi coat?” She exhaled a ragged breath. “I just want to die without pain.”

I had absolutely no idea where or how I would get the Xi yarn. “I’ll do it.”

“I’ll come back tomorrow night.”

“Tomorrow?” I laughed. “Wait, Vada. First of all, I don’t think the yarn is even still made. I would have to find someone who somehow still has some, get it here, weave it into cloth, and then make a jacket.” I waited for a reply, but none came. Whispering, I said, “Tomorrow is impossible.”

“You’re very talented,” she said, and turned away.

“Wait!” Irrationally, I was struck with a terror that I might never see her again, and even as I tried to choke the words in my mouth, I asked, “Did you ever really love me?”

Her body slumped, fabric pooling at her feet.

“I’m sorry, Vada.” I felt ashamed. I was unraveling before her. “It’s just that I’ve been thinking about what happened… mulling it over and… I’m sorry, I’m just in shock that you’re here.”

“Tane,” she said very quietly. “I must go. Please, I need the coat tomorrow.”

“Vada, tomorrow is impossible. I’ll try my best, but it will take days.” Even as I spoke, the rounded top of the cloth relaxed like a balloon beneath was losing air. Wrinkles and valleys appeared as the pile descended to the floor. She was collapsing before my eyes. Reaching into the fabric to grasp an arm or a shoulder, I found nothing but more wrinkles of the basketweave. I flung the fabric to the side, afraid I was going to uncover a puddle of flesh.

I found nothing.

Dropping to my knees, I pushed aside the cloth and felt the cool floorboards beneath. I turned my gaze to the showroom doors and down the curve of the hallway. The place was empty. And silent. It was as if I had been visited by a ghost.

Studying the floor where she had been standing, I discovered that one of the heartwood planks had been disturbed, the clear diamond-coat sealer neatly sliced along its lines. Yet as hard as I banged on it, I could not make it move.

“Vada! Where are you?”

Slumping to the floor, I heard the rhythm of my breathing, the air molecules being sucked into and pushed out my bronchi. I heard the rush of blood in my ears and the distant clap of my heart valves. She wasn’t the fool; I was—for believing and cherishing the impossible. Picking up the basketweave, I held it to my nose and inhaled. I smelled a mixture of rose, corn, and a hint of smoke.

PART 1 PLY

SEATTLEHAMA: A PECULIAR FASHION BUSINESS

When I am asked about my talents in the yarn arts, I like to say that there is no such thing as talent. When they ask how I came to be one of the world’s top designers, I shrug and mutter some cliché like hard work, luck, or perspiration. In an interview a year ago at FiberKon, someone asked when I knew I was a fashion genius. I told him I was not a genius. I believe that. But I do have a few special talents that no one else seems to possess. Maybe I always knew I was different, but it was during my first year in Seattlehama that I saw real evidence.

I showed up for work one morning to find my boss, Withor, standing over my little desk. The drawer was open and on the top sat my secret yarn collection that I had gathered over several weeks. It was significant to me, but wasn’t even enough to knit the toe of a sock. “Did you steal this from me?”

“No!” Withor was a cloth jobber who had an office filled with samples. “I found them.”

He grabbed a magnitron loop from his desk, held it between his eyebrow and nose like a monocle, and peered at the stuff. “These are all torn bits of junk!” Frowning, he asked, “Where’d you find them?”

“Just around,” I lied.

“You’re a thief! You stole them from somewhere. I should send you right back to the dirt!”

* * *

He meant the slubs, the vast corn-filled world that surrounded the city for thousands of miles in all directions. It was where I was born and had lived until I was nineteen. It was a world dominated by corn and sadness. I never wanted to return.

“I did,” I confessed. “I’m sorry.”

“From where?”

“T’ups.” I hadn’t meant to use the slubber word for city men, but he didn’t seem to notice. Shrugging, I added, “I just grab them.”

“You grab yarn from cloth?” He snorted. “Impossible!”

“It’s true. I can show you.”

In the hallway outside of his office, he pointed one of his long fingers. “The woman in the orange crinoline halo dress. That’s a half-denier yarn. I defy you to pluck one of those from her fat behind.”

I approached the t’up who stood before a showcase window of pewter, blackroot, and satellite ivory buttons and notions. The fabric’s yarn was incredibly thin, but I could see that the grid of the weave was at a forty-five-degree angle, and noticed a small twisted loop near the center seam that stuck out just a thirty-second of an inch. That was enough for me to grasp between my fingernails. With a snap of the wrist, I yanked out a bit, turned, and headed back to Withor and handed him the thing before she knew what had happened.

He studied it with his magnitron. “Unthinkable for the denier…” He tossed the thing to the floor. “Impossible! I demand you repeat it with someone else.” He scouted the crowd. “There! The gentleman in the green plaid, strolling suit.” He made me take a dozen more yarns before he believed that I wasn’t tricking him.

“Fine,” he said, and tossed the samples at me. “I’ve seen enough. You stole the yarn. All this capacity of yours amounts to debris only useful to a sparrow building a nest. It’s a disgusting frayed mess. They’re torn little bits of thing. Don’t do it again or I’ll toss you out!”

Withor’s dismissal stung, but over the next several days, as I looked at my collection, I decided he had a point. The ragged ends were ugly. Using several odd bits of metal, broken scissors, and wire that I had found in his office trash, I made two tiny sharp hooks. At first I tried to hold the tiny knives, but found it was better if I glued them just under my fingernails. Once I had practiced with them, I showed Withor, thinking he would be impressed.

He popped his magnitron on his eye and inspected my hand. “What’s the purpose of this? I told you to stop that disgusting yarn snatching!”

“They aren’t frayed anymore!”

He glared at me. “I really should have you sent back down to the slubs and get a slave who isn’t a criminal nuisance.” Then he eyed my fingers again. “You mean you actually cut a single yarn with those?”

“Yes.”

In the hallway, he pointed to a t’up in a butterfly hat, vermillion clack shoes, and a long white crepe floor jacket.

I ripped a high-twist yarn and handed it over.

“Ha!” he said, as he examined it with his magnitron. “I should have guessed. Cheap irradiated cellulose!” He let the magnitron drop from his eye socket and caught it in his right palm. “And indeed… it is perfectly cut.” Narrowing his eyes, he fiddled with the pin and bolt near his tie knot. “This is nothing! I could do it easily myself.” He stared forward for a beat. “Quite easily. Cutting a single yarn from cloth and extracting it. It’s nothing at all…”

Three days later, Withor directed me to sit in the guest chair across from his desk for the first time. “I mentioned that odd talent of yours to an associate,” he began in that languid rhythm of his as he fiddled with the bondage of his necktie. “Well, talent is not the right word. What you have is a perversion of sensibilities.”

From his desk he picked up a square of black cloth and kissed it to his lips. “I would have ignored him, but he is offering a substantial reward.” He set the cloth down and glared at me. “I fully expect that you will fail. You might even be maimed or killed.” He laughed dryly. “Such a tragedy that would be!” He leaned far back on his chair and spoke toward the ceiling. “Oh, I had such hopes for my life… for artistry and grandeur, but it has become overgrown with deals. And now another contemptible scheme has found me.” Sitting up again, he finished, “But I would be a fool not to investigate the possible lucrative side of your repugnant little ability. In any case, this associate happens to have a wet spot for the repulsive and saccharine Tinyko 200. Namely he wants a bit of yarn from her little puff skirt.”

It would have been impossible to escape Tinyko 200. As the Celebrity Executive Officer of Bias-Anderson-Commonwealth¬Burlington-D her image, sounds, and brands saturated the city in the form of engineered alloy, fan engines, pumps, diagnostics, extruders, fabricators, and a popular line of dresses, gloves, eyeglasses, and radio underwear. Tinyko herself was a tiny, young woman with wide blue eyes and a pert mouth. She was famous among the young Cute Bubble Active style girls, but since her recent birthday, had started venturing into the mature market, or as it was called, Wetting the Show.

So that I would blend in as an IMG collector, Withor bought me my first suit and tie. I remember staring into an audience of mirrors and marveling at how I looked. I was no longer a boy, a slubber, an indent worker, but a city man. To finish my costume, Withor also bought me a knit mask. “IMGs wear these silly cloaks, so you have to too.”

The thing was like a super-fine stocking made to fit over the head and obscure and soften the features. With it on, I looked like a mannequin. With the necessary pass in hand, I headed to the banquet hall at the top of the city, and slowly worked my way toward the stage.

The others all held their photo-cams, sight-cannons, airtricity gauges, infra-and ultra-meters, waiting for a glimpse, a peek, for the chance to cut an image of Tinyko’s tongue momentarily caught between the raspberry of her lips and her milk-glass teeth, her soft fuzzed cleavage as she leaned forward to laugh, her delicate and slender fingers frozen in an inappropriate pose seemingly about to caress the tiny spike of her left nipple through a silken skullcup of a bra.

Beside me in the crowd, another masked man said, “Last show, I got a shot of her crotch so tight you can smell the salt scrod of her cut.” He smacked the black, dimpled barrel of his cam and laughed. I nodded as if in appreciation but soon slipped away. His passion seemed desperate and alien.

Moments later, atom lights flashed. Torrents of blue smoke shot from around the crystal stage and the thundering beat of Tinyko’s newest song began to vibrate my gut. A phalanx of dancers and strippers ran out and genuflected as from the center came a roar of a fan-jet and there, in an elongated bubble of orange light, was Tinyko. She waved at the crowd, flashed her fluorides, and then opened her mouth wide and screeched her first note with an ultrasonic intensity. One of her slender fingers riffled through the chiffon at the front of her skirt and for a split second revealed the glistening ultra-white of her radio panties. Like piranha, the crowd pressed forward and spattered her face, chest, and crotch with ricocheting white, green, and pink flashes.

Going sideways, right shoulder first, I jockeyed through the men, pushing an elbow here, nudging against a moist twill there, and made my way toward the right side of the stage where the stairs were guarded by a dozen men who wielded smoking-hot scimitars. Between the men sat black guard dogs with long hypodermic teeth. According to the program, after her flash song, she would come down the stairs, let several fans feel her breasts, and auction off a thimble of her virgin love-juice. It was then that I had my best chance to get close enough to rip a yarn from the puff around her nineteen-inch waist.

As I got closer, it actually became easier to swim through the bodies because most of the others were pushing themselves under the lip of the clear stage and pointing their lenses up. And just as I reached the edge of the long glass stairwell, close enough to smell the rubber and asbestos of the guard’s safety jackets and the red-hot of their curved blades, she started down.

Her steps were shaky and clumsy. And up close, I could see the depth and opaqueness of her theatrical make-up, her horsehair-thick lashes, and the way her lipstick was drawn beyond her natural lips. In person, she seemed small, artificial, and awkward.

As she came to the bottom of the steps, I squatted, and when she neared, reached between the legs of one of the guards toward her skirt. The infinity chiffon was the softest thing I had ever felt. It was like fresh corn silk and distant whispers and I touched it a split second longer than I might have just to experience its excruciatingly tender hand. I couldn’t see my fingers in the haze of the fabric, but found one of the micro-denier yarns, cut it and yanked it. Next, I dropped to the floor and twisted away just as the thick arms of one of the guards twitched. He smashed his scimitar blade a foot deep into the carbon-cement floor right next to my ear.

Standing, I turned and pushed my way through the worshipping throng, my heart pounding.

SEATTLEHAMA: THE VOLCANO-POWERED SEX AND SHOPPING CAPITAL OF THE WORLD

I looked up at the city of Seattlehama every day of my nineteen years in the slubs. The mile-tall circle of buildings—constructed atop Mount Rainier—was often just barely visible in the ginger haze of the morning sunlight. During the days, as I worked in the corn, the towers split the yellowed sky and tore long holes in cloudbanks. And at night, I would often sneak out and stand in the dark of the fields and the dilapidated and unlit houses where slubbers slept dozens per room and watch as the sky faded to charcoal and purple and the curves and spikes of the towers gleamed like the frozen flames of an enormous rocket ship heading straight into the heavens.

Years later I would learn that the ring of skyscrapers of Seattlehama were not like the tall buildings of other cities. Instead of glass-covered boxes, these were built of woven ceramic. Up close they were covered with fabriclike patterns. Not only was each strong and flexible in ways that older buildings weren’t, but the city was built around a mile-wide atrium with the circle of buildings all linked in such a way that supported and was supported by all the others. I’ve heard it said that half the city’s towers could be removed in an instant and the rest would barely sway.

* * *

For my first six months inside Seattlehama working for Withor, I lived near the bottom, just a few floors above the simmering pools of the lava that was drawn from Mt. Rainier to power the city’s massive turbines. The place was known as the slubber slum, where several hundred brandclanners lived in a dozen dim sleeping and eating cafés. Most of the men worked below with the toxic biofilms that held back the lava, replaced valves on the steam turbines, or fixed the pipes and made repairs on the dark undercarriage of the city. My cleaning and errand-running job with a textile jobber was unusual, and I never mentioned it to the men who returned from the day filthy and bleeding.

In many ways the ghetto was worse than the slubs. There was no view, no sky, no sweet scent of the ripening corn tassels in the fall. It was filthy and uncomfortable. The food was awful. And worst of all, the slubber transplants grew angry, fidgety, unsettled, and unpredictable.

“Watch it, soy boy!” someone would shout.

“You’re a corn smut!” another would reply.

Each night it was always the corn-eaters versus the soybeans versus the potatoes, all crops of the major brandclans. Soon someone would throw a punch or a kick and a melee would rage until men in purple satin came in and beat everyone with their long electric sticks. And every few days someone died at their job, or was bashed over the head by the satins, or just didn’t wake up. The next day a new man from below was brought up to fill his place.

But the instant I had handed over the pale, almost weightless and invisible yarn from the chiffon puff from Tinyko’s skirt, everything changed for me.

“Excellent condition,” said Withor as he examined it under his magnitron. He cackled brittlely. “I have three more orders for yarn plucked from the sad asses of our city’s blessed corporate celebrities.” He glared at me. “You will snatch them as quickly as possible.”

While I thrilled at the idea of taking more yarn, I knew I was being used. “What do I get?”

“You’re a slubber! You should be happy just to be in our glorious shopping city, away from the retched squalor of that corn all around.”

I stared at him unhappily.

“What you do is trivial. Trivial and trifling. I could certainly do it all myself—and much better—if I so chose.” His right hand fiddled with the pins on his black-and-white-striped tie. He flit his hand in the air. “Keep that suit and tie.”

While I loved my first suit, I shook my head. “The yarns I take are worth more.”

“You’re a corn slubber! You’re a fly! You’re a lint caught in the ass crack of another lint! And you don’t tell me what something is worth. You don’t negotiate with me! You don’t even beg. You take my orders and you carry them out and you are glad.”

I worried that I had gone too far. In the beginning I had been impressed with Withor as I had with everything in the city. And while I now secretly hated him, what he said was true. Below my suit, minus my yarn ripping, I was a slubber. I was lucky to be away from the drudgery, the labor, and the politics of life in the corn.

“Fine!” he sighed. “I’ll give you point one percent of net.” From a drawer he pulled out a small rubbery purple card and tossed it at me. “And with that you can purchase all the trinkets and trash you can… well… you can afford. All of Seattlehama takes MasterCut.”

At the end of the day, I was heading down the familiar stairs that led to the slubber ghetto when I stopped, and fished the card from my pocket. The purple surface was tacky and shiny, and if I tilted it back and forth, I could see a t’up inside it wearing a strange stringy shirt that cut lines across the neck, shoulders, and swollen chest. Below, I heard someone shout, “Soy boy, play with your tiny toy!”

Someone else yelled, “You’re corn rot!”

Tucking the card into a pocket, I adjusted my lapels, tightened the knot in my tie, and turned to the city proper. I wasn’t a slubber anymore. I had a fashion job collecting valuable yarn. And most of all I had a purple MasterCut!

The first thing I did was head to a store called The Highly Profitable Epicurean Frosting Franchise not far from Withor’s office and order a Chocoa 99.71%. I had seen dozens of t’ups walking around gleefully stuffing themselves with the stuff. The sticky brown paste came piled high in a double-D bra cup and was served with a long ivory spoon. It was a dozen times sweeter than M-Bunny cola and like nothing I had eaten before. After just one spoonful, the sugar and butterfat coated my mouth. After three, a buzzing nervousness trembled my fingers and my stomach was filled with lead. I dumped the rest in a noisy and blinking entertrash basket.

Still, the joy of holding up my MasterCut—as I had seen Withor do when purchasing notions for the office—and having the t’up behind the crystal counter nod and then hand over the frosting confirmed everything I wanted that day.

Down another hallway I found the cloth stores. Inside it seemed a rainbow of everything I had ever wanted to see, touch, feel. I found black cloth so black it didn’t seem to exist. I saw colors so bright they hurt my eyes. I saw wools, polys, cottons, rayotts, pricons, flaxes, silks, bamboos, and metals. I smelled cashmere, flax, ramie, abaca, basalt, and camel. I marveled at the crispness of the satellite silks; the springiness of the spandicotts, the softness of the French puff-flannels. I inhaled the starch in the taffeta. I rubbed crepe on crepe and enjoyed the sandy grit.

From there, I found a thread and yarn store and laughed out loud at the thousands of colors, sizes, twists, weights, sheens, lusters, plies. This was more than I had dreamed of. This was more than I had ever imagined. I read a sign that said: 46,231 more shades of red available by special order.

In another store I found fashion machines: acoustic jacquards, card punches, loom beams, air-jets, deweavers, flash seamers, water-knitters, flux steamers. Standing before a Control R&H projectile loom, I traced my eyes as yarn might travel along spool holders, through weft tensioners, across conveyor wedges, up and over shedding boxes, through eyeholes, down to spindles, the tooth blocks, guide scissors, and out of the heddles through the wormwheels.

I ran a hand over the smooth brushed finish, the marbled gray paint, and solid brass fittings of an A-Max insta-seamer. Turning, I found a clearing and five feet from me, a t’up stood on a knitting machine that resembled a ski trainer with two long hand poles and foot levers. The t’up pushed one pole to the right and spun the other. A set of floating hooks knit blue yarn into a pair of shorts in midair. I wasn’t sure how it worked exactly, but decided that the left pole steered the knitting hooks and the other controlled the number of loops.

Three others stood watching. One wore a white suit and held a thick, jewel-encrusted cane. The second wore all black, but here and there on his jacket were small live, wiggling white worms that had been woven into the fabric. The third, in a camel hair suit, had what I later learned was a giraffe mask over his head.

The knitting t’up pulled the right handle to the side. Now a thicker band was formed around the top of the shorts. A moment later, the t’up pulled the right stick far back, pushed on the right footpad, and the machine stopped.

“Artistic zeal!” said the man in white. “Flamboyance and bravery!”

“Best britches for bitches!” enthused the giraffe. “May I?”

Using a pair of connected needles, the t’up took the shorts from the machine, seemed to knot it, and handed the shorts to Giraffe.

Curious, I stepped forward. “What is this?” The four of them turned and looked at me with varied amounts of confusion and disdain.

“This,” intoned the man in white, “is the Stanton-Bell Tex¬knitter 222. It’s the top-of-the-line artesian, topsumer, craft¬gasmic, model with the skivvé form.” He blinked several times. “Welcome to my fashion motor boutique. Call me Archibald. Are you… um… are you a knitter?”

My confidence faded. “No. But I think I saw how it works.”

“You have fine taste, good consumer, sir, but I wouldn’t suggest starting on a stand-up Tex-knitter. We have desktop models for socks, collars, and wrist bands for crafters in all sorts of pleasant and complimentary colors.”

Meanwhile, Giraffe was tugging the shorts on over his pants. Only they weren’t just shorts, but the front had three pouches: one long and two smaller ones for a root and two nodes—that’s what slubbers called genitals. And his root was eleven inches long.

“I am the corporate executive slut of my dreams!” said Giraffe, shaking his hips back and forth. “Watch my fantasy grow!” They all laughed.

Meanwhile, I was studying the t’up who had been on the knitter: the shape of the eyes, the smoothness of the neck, and the contours of the body. She was definitely not a man.

When she wiggled her hips, the long root tube on her identical shorts flopped back and forth. She said something about scratchy yarn and while they laughed again, I stepped backward. If someone had inspected the tag at the back of my neck that instant, it would have read: 50% confusion 30% fright 20% arousal.

* * *

In the slubber ghetto the main topic of conversation, besides which crop was best, was about the existence, features, meaning, and anatomy of Seattlehama women, or what we called reds.

I was born into the M-Bunny brandclan and we were the planters of corn. Our special crop dominated the hills around Seattlehama. To the south, L. Segu, the soybean clan, was stronger. And while we had our differences, we had several things in common. For one thing the slubs were filled with men and nothing but men. Men planted the crops, tended them, harvested them, processed them, made them into all sorts of things, ate them, and recycled them. Men cleared old roads, tore up old parking lots, razed useless buildings, and planted more corn.

But once a year, a few men who worked the hardest, praised the crop the most, and recycled everything they could were rewarded with the opportunity to have a son. They boarded one of the buses and traveled to headquarters. They wore different B-shirts there and ate something called krissmascake. They thought that it was those cakes that made their roots hard. And when that happened, a red would come and would lay down with them.

Ordinarily, no one in the slubs had erections. The only exceptions were those who traveled to headquarters, those who were debranded, and those few who, for some reason, had just gone corn rot. If a rep caught you with a hard root, it was said you would be immediately debranded or just recycled, but I never saw it happen.

It wasn’t until years later that I understood that those B-shirts and shorts we wore muted our tempers, our anger, and mostly our libido.

* * *

I don’t know if she sensed the surging of my heart, but the t’up turned and addressed me. “Shopper…” Her eyes darted over my Teardop suit. “From what finger of the glove have you come?”

I didn’t understand finger of the glove, but feared it had something to do with the slubs. “No,” I told her. “I’m… um… I’m just here looking.”

“Adrift,” she announced to the others. “Adrift in the currents of commerce and unfamiliar with the loft and ply of fashion.” Her glossy red lips pinched off what seemed like a growing smile. “Shopper, have you never envisioned skivvé?”

The man in the giraffe masked said, “That’s Python Duck Weapon’s Celebrity Executive Officer, Kira Shibui.”

“I am Tane Cedar,” I told her. My heart was beating hard and my palms were moist. “You knit syrup.” I had inadvertently used a slubber word. “I mean… great!”

Her right eyebrow rose with curious skepticism. “A small but curled wood shaving of praise.” She eyed the others. Worm Jacket giggled. Giraffe nodded.

They were laughing at me. “I am also interested in yarn and knitting.”

“If you desire, Kira,” offered the storeowner, “I’ll ask him to leave.”

She held up a gloved hand. “Allow him to linger.” She narrowed her eyes. “Those who harbor hearts that beat not with the liquids of the pedestrian, but with twists of the fiber… we must always show honor.” She squared her shoulders and stared at me intently. “I am a saleswarrior for Python Duck… in the glorious skivvé battles amid the grand foundation war.” When she inhaled, her breasts were squashed inside her rather stiff-looking outfit. I didn’t know how to describe it at the time, but it was like a sailor suit in shiny orange decorated with several large bows. The flared skirt was so short it didn’t cover her underwear. The neckline was low, and around her neck rested a wide collar. Her boots and gloves were the same orange. She peered at me. “You must know the glory, dear mislaid shopper.”

I didn’t know what she was asking, but was glad to have her gaze on me.

Her red lips tightened. “Then know this citizen of credit: we of Python Duck are fighting against the keepers of the dark, the wearers of the empty, and the besmirchers of the cloth. We freed ourselves to oppose the awful howl of the gathering void that is Casper Union!” She screamed the last two words.

“Casper Union? What’s that?”

My question seemed to please her. She turned to the others. “And thus with his genuine confusion, I have freed him from the realm of the counterfeit and the spy.”

“Oh, well done, Kira!” said the man in the worm jacket.

“Brilliant!” Giraffe bobbed his head in a nod. “I didn’t even think that he might be an enemy spying on us!”

“Now we know,” said Kira, raising her voice, “that he is simply from the dim and the dark bones of fashion.” She turned and gazed at me with warmth and sympathy. “Someone should mental him in the ways of the lapel, the seam, and the blessed undergarment.”

I knew she was making fun of me, but it didn’t matter. “I want to learn.”

“Then let me unfold one sleeve of the truth: Casper Union is the skivvé maker that cares not for anything but the lack of their own make.” She held up a fist. “They are stealing the glory… No! They are tarnishing anything that was ever coated with even the thinnest skin of commerce and pride.” Pointing a finger at me, she said, “New friend of our sex and shopping city, you must study fashion and its wars. Come to my flagship: Python Duck on level 609 in the Velour Building and behold the fine art and craft of men’s fantasy skivvé.”

“Best britches for bitches!” said Giraffe.

“We are desperate for fashion passion!” she continued. “And we are desperate for cutting and needling.” She turned her face toward the others. “We need the commanding and the strong and the vigorous to help wage the terror upon those with shallow and muddy puddles of soul.”

“Muddy puddles of soul!” whispered the man in the worm jacket, nudging the giraffe.

Returning her attention to me, she asked, “Do you, shopper Tane Cedar, with a proud and curious interest in knit—do you have the formidable vision? Do you have clarity of duty? And most of all, do you have the valor to test the capricious needles of destiny?”

Worm Jacket and Giraffe and even the storeowner turned to me. My eyes leapt from Kira to the others and back again. I swallowed and said, “Yes?” hoping that was the right answer.

“Kira Shibui, Celebrity Executive Officer of Python Duck Men’s Fantasy Skivvé!” boomed the storeowner. “Visionary knitter, designer, and warTalker extraordinaire. She truly warms the new Stanton-Bell Tex-knitter 222!” He ran a hand along the top of the machine. “I will have this sent to your flagship tonight!”

Worm Jacket and Giraffe began talking excitedly as the storeowner rambled on with numbers and jargon. Meanwhile, Kira’s eyes lingered on mine.

“Kira Shibui,” I whispered, happy to have remembered her name.

She didn’t exactly smile, but something deep in her eyes seemed to warm. Turning, I headed out of the fashion motor boutique. My hands were vibrating, my heart was racing, and I felt like I wasn’t getting enough air. In the hallway, I stood for a moment and caught my breath. I didn’t know what was happening, but my root had stiffened for the first time.

Yarn © 2010 by Jon Armstrong

dammit. now i wanna buy the book. thanks a LOT.

Yarn, meet to-read stack. To-read stack, meet Yarn.

Man, I had forgotten how delightful Jon Armstrong’s craziness was! His writing mind works in really strange ways, but judging by his other book _Grey_ good plot still comes out!